Factors Affecting Resident Satisfaction in Continuity Clinicã¢â‚¬â€a Systematic Review

- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

Do virtual renal clinics improve admission to kidney intendance? A preliminary impact evaluation of a virtual dispensary in East London

BMC Nephrology volume 21, Article number:10 (2020) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Early identification of people with CKD in primary care, particularly those with hazard factors such as diabetes and hypertension, enables proactive management and referral to specialist services for progressive illness.

The 2019 NHS Long Term Plan endorses the development of digitally-enabled services to replace the 'unsustainable' growth of the traditional out-patient model of intendance.Shared views of the complete wellness information available in the master intendance electronic health tape (EHR) can bridge the divide between main and secondary care, and offers a practical solution to widen timely admission to specialist communication.

Methods

We describe an innovative customs kidney service based in the renal department at Barts Health NHS Trust and four local clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) in east London. An impact evaluation of the changes in service commitment used quantitative data from the virtual CKD clinic and from the chief intendance electronic health records (EHR) of 166 participating practices. Survey and interview data from health professionals were used to explore changes to working practices.

Results

Prior to the start of the service the general nephrology referral rate was 0.8/k GP registered population, this rose to 2.5/1000 registered patients past the 2nd year of the service. The majority (> lxxx%) did not require a traditional outpatient appointment, but could be managed with written advice for the referring clinician. The await for specialist communication fell from 64 to 6 days. Full general practitioners (GPs) had positive views of the service, valuing the rapid response to clinical questions and improved access for patients unable to travel to clinic. They also reported improved conviction in managing CKD, and high levels of patient satisfaction. Nephrologists valued seeing the entire primary care record but reported concerns virtually the book of referrals and changes to working practices.

Conclusions

'Virtual' specialist services using shared access to the consummate main care EHR are feasible and tin expand capacity to deliver timely advice. To use both specialist and generalist expertise efficiently these services require support from community interventions which engage master intendance clinicians in a data driven plan of service improvement.

Background

In the adult UK population the estimated prevalence of Chronic Kidney Illness (CKD) stages three–5 is 5–six% [1]. Identification and coding of CKD in principal care provides a example register which can be used to back up the active direction of claret pressure, cardiovascular take a chance and safer prescribing. A register also enables regular review of CKD and specialist referral where there is diagnostic doubtfulness or show of progressive disease [2].

At that place is some show that lowering blood force per unit area can delay the progression of CKD [3, 4]. The loftier rates of cardiovascular risk associated with CKD tin can be reduced by advising the utilise of statins and improving control of claret pressure [5].

Currently most 70% of health and social care budgets are directed towards the care of people with long term conditions [6]. The NHS Long Term Program, released in 2019, envisages efficiencies in the direction of chronic diseases and major changes to the delivery of hospital outpatient care which is described as outdated and unsustainable. It endorses digitally-enabled master and outpatient intendance, which 'will go mainstream beyond the NHS', and 'will costless up meaning medical and nursing time'. [vii]

A number of Uk studies describe a variety of virtual renal clinics which include alternatives to confront to face up consultations. Harnett et al. describe discharge from a general nephrology clinic into virtual follow-up, with regular examination monitoring organised past the infirmary and communicated to the patient's GP [eight]. Jones et al. depict a shared main-secondary care scheme with nephrologists monitoring the test information recorded in primary care [9]. Mark et al. triaged less-complex referrals to virtual biochemical surveillance, and demonstrate the cost saving compared to routine dispensary attendance [x].

Other approaches which use structured exam monitoring independent of clinic attendance include eGFR graph surveillance by laboratory staff, this is specifically designed to identify those with progressive CKD and encourage onward referral [11].

In contrast with these schemes, which are run from infirmary clinics, the east London community service includes dashboard information on every GP registered patient with biochemical show of CKD [3,4,v], non only those referred into renal clinics. It has an emphasis on upstream CKD management in primary care (claret force per unit area control and statin prescribing) with benefits for reducing the risk of cardiovascular affliction associated with a declining eGFR [12]. All general nephrology referrals from GPs are assessed in the virtual clinic. The dispensary aims to support the direction of less-complex CKD within the framework of primary care management of long-term conditions, by providing timely advice, but restricting traditional outpatient clinic follow up to the modest number of progressive cases which crave more intensive specialist management.

Aims

a) To describe the development of a virtual CKD clinic prepare within a community kidney service which integrates data across primary and secondary care, based on the concept of a learning health organization – in which the data from every patient encounter is used for system development and improve do [thirteen].

b) To evaluate the impact of the virtual CKD clinic on timely access to specialist advice, and on satisfaction with changes to service delivery by chief intendance clinicians and renal specialists.

Methods

Study design and setting

This observational report was set in east London master care and the Renal Unit at Barts Health NHS Trust between 2015 and 2018. Barts Health NHS Trust is the sole tertiary renal provider for North-East London, reporting a high incident need for renal replacement services, with over 30% of patients with new end stage renal disease commencing dialysis in an unplanned manner, compared to 15.6% across the Great britain every bit a whole [xiv].

All 130 GP practices in the three contiguous inner east London clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) co-terminus with their London boroughs of City and Hackney, Newham and Belfry Hamlets (total population 800,000) were involved in the get-go phase of the service change during 2016, with 36 practices in Waltham Woods CCG joining in 2017. All practices use Egton Medical Information Systems (EMIS Web) for the patient electronic health record. In the 2011 U.k. Census, about half of the population in each of these CCGs was recorded to be of non-white ethnic origin [xv], and the English language indices of deprivation 2015 prove that all three inner e London localities fall in the lowest decile for social deprivation in England [16].

Theoretical stance

Many of the strategies for change management described by Kotter [17] were used in developing the design and implementation of this plan. These include: building the example for change and forming a guiding coalition which includes both clinicians and managers, empowering others to act on the program by providing clinical data, quality improvement (QI) tools and comparative performance data, ensuring that there are early wins for the plan and edifice sustainability for the future by embedding the new approach into work as usual.

We are likewise aware of the importance of local context in determining the uptake and successful implementation of change. This project builds on previous experience of successful quality improvement projects in participating CCGs.

Description of the E London community kidney service

The customs kidney service had three components described below. This report focuses on the evaluation of the virtual CKD clinic.

ane) The virtual CKD clinic: this takes electronic-simply referrals from GPs for general nephrology communication into a weekly hospital dispensary serving each CCG. Service development included the introduction of the EMIS Spider web platform to the renal unit and sign up by all practices to information sharing agreements to allow nephrologists to view the consummate primary care electronic health tape (EHR), with informed patient consent. This facilitates review of eGFR plots over fourth dimension, proteinuria and all recorded investigations, examinations, medication history, co-morbidities, hospitalisations and other specialist in- and out-patient documents.

Following review of the notes, nephrologists tape communication in their version of EMIS Web, which is immediately available for all clinicians in the practice to view. On average each virtual consultation took twenty min, this compares to a offset omnipresence out-patient template time slot at Barts Health and other Renal Units of 30 min per new patient for a general nephrology consultation. GPs are advised when the nephrologist has 'seen' their patient past an alert inside the EMIS workflow module. The dispensary has a short wait time with the aim of providing timely clinical advice for GPs. Nephrologists triage the minority of patients who crave further investigation into traditional, face to face, general nephrology out-patient clinics. Each CCG community clinic has ii–3 named nephrologists, with the aim of edifice positive clinical relationships between GPs and hospital based specialists.

Each participating CCG agreed additional pilot funding to initiate these changes to the renal service. The appetite was to fund the service as a block contract based on the previous years' general nephrology activeness. The NHS Long Term Program increasingly commissions for whole pathways rather than itemised episodes of care. The per CCG contract for the virtual organisation was priced at an annually reviewable, fixed tariff for all activity, including education, developing and delivering dashboards, and do facilitation. Hence the Renal Unit of measurement carried the risk of growth in appointments and activity above baseline, with CCGs holding the risk of the service contracting traditional outpatient activity and GPs providing more extended direction in primary intendance settings. In addition each CCG developed customised local enhanced services (activity additional to the GP core contract [18]) with financial incentives to promote best CKD direction (treating claret pressure to target, apply of statins for secondary CVD prevention and monitoring CKD progression.) Quarterly dashboards identified the number of patients with evidence of CKD, changes in do performance in CKD coding and management, and were available to practices, commissioners and the renal department.

The first virtual CKD clinic for patients in Belfry Hamlets, based at the Royal London Hospital within Barts Health NHS Trust, went live in January 2016. Curlicue out to Newham and Urban center and Hackney took place half-dozen months later, and Waltham Woods joined the programme in 2017.

The other elements of the community service included: 2) A package of It tools: these enable practices to identify patients who require diagnostic coding, would do good from better blood pressure control, or an offer of statins to decrease the risk of cardiovascular disease. They also include monthly do alerts to identify patients with a falling estimated glomerular filtration charge per unit (eGFR). The 'falling eGFR trigger tool' reports patients with an eGFR < 60 who on series testing have a refuse in MDRD-measured eGFR of ≥10 ml/min [19]. Regular practise facilitation sessions roofing clinical data management and the apply of project specific It tools were provided past the Clinical Effectiveness Group (CEG) https://www.qmul.ac.uk/blizard/ceg/renal-health-service/). Extra clinical support by specialist renal nurses, with a focus on CKD management, was offered to do teams which had the lowest rates of CKD coding.

c) Renal education: regular updates and case discussions for general practitioners and exercise nurses were held at CCG and practice events in all iii project CCGs, with specialist renal nurse-led patient teaching sessions for patients referred into the service [20].

Information sources for evaluation of the virtual CKD dispensary

Data on referrals, appointment numbers, cost and type (whether virtual, traditional full general nephrology outpatient showtime or follow up attendance) and wait time were nerveless from the care records arrangement (CRS) at Barts Health NHS Trust. This was supplemented past nephrology department data on transfers betwixt virtual and traditional appointments, and on renal follow up of patients in the virtual clinics.

Anonymised data on do coding and principal intendance management were collected on a quarterly basis through EMIS Web and collated into practice and CCG level dashboards.

Questionnaire survey data from Tower Hamlets GPs (the pilot locality for the virtual clinic service) was collected presently after the clinic went live and before the service had become 'work equally normal'. This data was enriched with interviews with GPs recruited from Belfry Hamlets practices, and all three nephrologists involved in delivering virtual clinics. These individual interviews with vii GPs, three nephrologist and ane CEG facilitator were recorded and transcribed and a thematic analysis using the Framework arroyo was adopted [21, 22]. Two members of the research team reviewed the text to ensure trustworthiness of the data. The thematic analysis focussed on the perceived benefits and limitations of the new service. The survey questions and interview topic guide are shown in Additional file i: Table S1.

All data were anonymised and managed according to UK NHS data governance requirements. Ethics approval was not required for this service evaluation, equally all patient-level data are anonymised, and only aggregated patient information are reported in this study.

Results

In the iv face-to-face participating CCGs of Tower Hamlets, Newham, City & Hackney and Waltham Forest, with a GP registered population of one.2 meg people in 2017, there were 21,560 adults with biochemical evidence of CKD (stages 3–five) at the mid-bespeak of the study. This population prevalence of 1.8% is similar to that of London as a whole (ane.9%). The effigy reflects the immature London population, and probable under ascertainment of CKD. The dashboard showing variation in CKD coding rates and principal intendance management of CKD across the four CCGs is shown in Tabular array ane.

The majority of practices engaged with the IT tools, and inside the first year CKD coding rates improved, with the everyman coding CCG improving performance past fifty% [23].

Referrals to the virtual CKD clinic

From the get-go of the service all routine general nephrology referrals from GPs were processed through the virtual dispensary. GPs were encouraged to refer anyone they would previously take sent to out-patients, and received local guidance which conformed to the 2014 Prissy CKD guidelines [2]. The 'falling eGFR' trigger tool, run monthly in practices, also identified cases to be considered for referral, on average viii% of trigger tool cases were referred to the virtual dispensary.

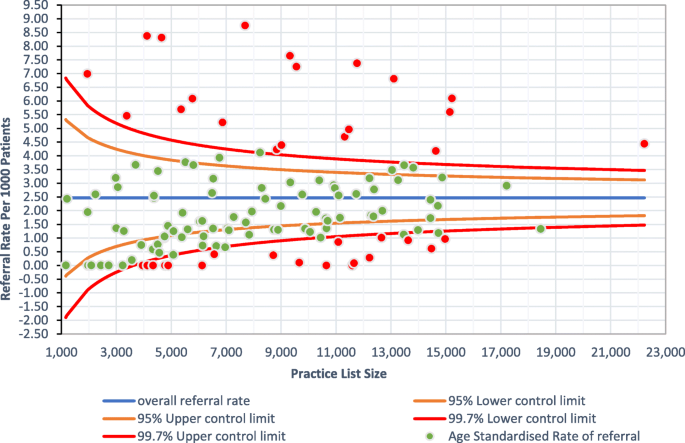

In the 12 months prior to April 2015 the average annual referral charge per unit to full general nephrology outpatient clinics was 0.8/k GP registered population. Past the second year of the service (2018) the average, annual referral rate was two.5/1000 registered patients as shown in the funnel plot (Fig. 1). This graphic shows that 15% of practices barbarous outside the upper command limit for referrals, and four practices with a list size > 9000 made no referrals during the year.

Annual (2018) age adjusted referrals to the virtual CKD dispensary from 130 participating practices in east London.* *Do populations age standardised to the East London population at the study mid-signal.

Dispensary information

The average waiting time from GP referral to a first outpatient appointment in 2015 was 64 days. When the virtual clinic started the average time between GP referral and virtual clinic assessment vicious to 4–6 days. The nephrology opinion can be viewed in the GP record on the 24-hour interval it is written, and a dispensary notification is sent electronically to the do inside a few days.

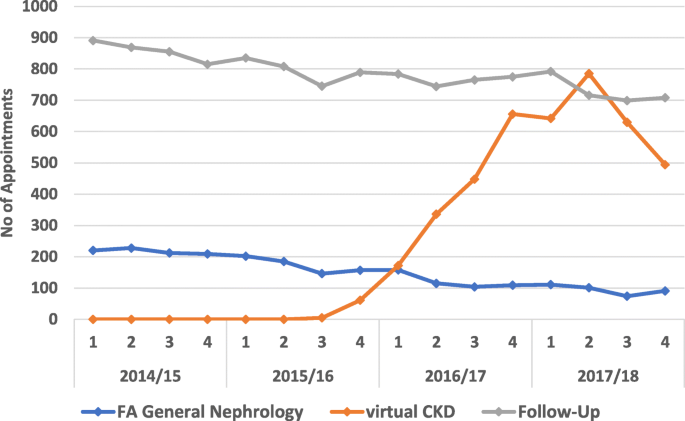

Effigy 2 shows the rapid take upward of the virtual clinic with an unexpected threefold rise in appointments over the showtime ii years of the service for all four CCGs combined. (Boosted file 1: Figure S1. shows appointment details for each of the iv participating CCGs). Over the 2 years following implementation the number of showtime general nephrology outpatient appointments had halved, and the number of follow-upwardly appointments showed a steady refuse. These changes have released general nephrology clinic appointments to be used for closer review of specialist and more complex cases.

First appointments in general nephrology, numbers of virtual dispensary and follow-up appointments for all participating practices in east London: quarterly 2014–18.* *Financial year quarters.

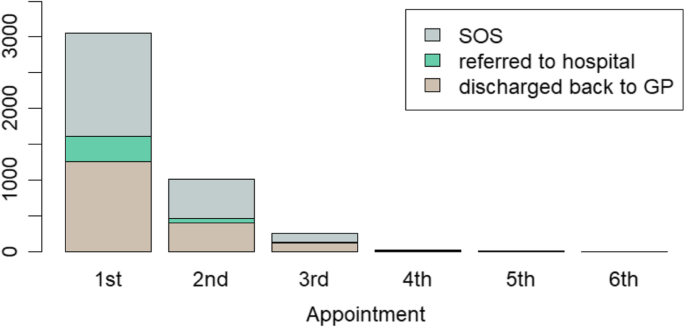

Across the whole service nephrologists conform an outpatient face-to-face review following just 12% of virtual appointments. Over 40% are discharged back to the GP, with upwardly to 50% being tagged for a further specialist review in the virtual clinic (see Table 2).

Information technology was as well possible to mensurate the 'hidden work' associated with virtual clinics by observing the repeated virtual reviews done by nephrologists. More than than 40% of initial referrals had a second virtual review, and thirty% of these had a third review (Fig. 3). The repeated review of virtual referrals was often linked to requests to GPs to arrange farther investigations to facilitate a more than consummate assessment. This virtual review work made upwards approximately 50% of a virtual clinic session, and alongside the early surge in new referrals contributed to a perception of overload past nephrologists. This work was not transparently captured by routine infirmary recording systems.

Virtual Clinic outcomes by first and follow upwards virtual appointment for the flow April 2017 March 2018 for all iv CCGs.* *The vertical axis shows the number of appointments, the horizontal axis tracks the number of virtual appointments for private patients. SOS = review appointment in the virtual clinic.

Survey and interview data

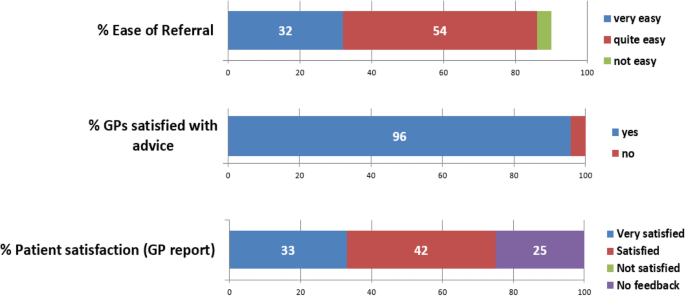

During the kickoff year of the service a questionnaire was sent to all 68 GPs in Tower Hamlets who had used the virtual dispensary. At that place were 28 (41%) responses, with 86% of responders reporting that it was very or quite easy to use the service and 96% being happy with the referral advice they received from the nephrologist (Fig. 4). GPs reported that about patients were satisfied with the service although ane quarter reported no feedback from patients. The overall value of the new kidney service was rated every bit five/5 by 60% of respondents.

Virtual CKD clinic survey in Tower Hamlets CCG (28 responses from 68 GPs)

Key themes from the interviews

Benefits for patients

Every GP interviewed said that all patients had readily consented to their records existence shared, with many expressing surprise that this was not already happening:

"I recollect the organization is great, and keeping people out of hospital is clearly a good thing."

Some GPs described how patients were now being referred when they had not been in the past:

"It is useful to go a bit of communication. In the by I would probably have not washed anything to be honest….every bit they (the patients in the nursing home) were not fit enough to go upward to hospital"

The timeliness of the referral was too considered of import for patients.

"Having the nephrologists seeing people within one week is a groovy benefit."

Finally, a number of GPs spoke nigh how the new system was educating them in managing CKD in the hereafter.

"The quality of the information coming back is proficient….I sympathize a bit more than now virtually the tests."

Working relationships between primary and secondary care

Many GPs spoke of the improved relationship with secondary care, particularly in terms of better communication and improved continuity of care:

"We have never met these people (the nephrologists) merely I feel I accept a relationship with them now….yous cannot underestimate that."

"The personal contact – I become the impression that there is better continuity as there is a named nephrologist."

Nephrologists reported that in the old system, some patients were referred only did not actually need to be seen, ofttimes in that location was no referral letter and up to half the fourth dimension there were incomplete notes in clinic. Other challenges included the duplication of tests, not knowing the medication list, transport or language difficulties.

"What I was non doing was anything meaningful."

The referral procedure is now easier with quicker response times. The ability to see the full tape, including all tests and correspondence allows a more in-depth case-review. From the nephrologists' perspective this can be challenging. Virtual reviews take about the aforementioned fourth dimension as an outpatient slot, and for some there is a sense of regret equally patient contact has diminished:

"The workload has surprised me…. It is a lot - I spend probably the same amount of time…x new patients in 4 hours."

"You do miss the sense of the person…y'all don't have the same sense as if someone is sitting in front of you."

There was a new respect for each other'due south role. One said of the former system:

"At that place was no thought in my heed that I would belch them back to the GP with an agreed common plan."

but now:

"That was a big mind shift for me, GPs and nephrologists don't often run into each other's piece of work of value."

The key messages are that patients are content to share their primary care record with nephrologists, and so that management communication tin be obtained without needing a visit to the hospital. The service provides timely advice back to GPs, who value the improved relationship with the nephrologists. One nephrologist ended by maxim:

"There's a lot of kidney disease out there that we did not know anything about."

Give-and-take

Master findings

Over a three year period this project developed a complex intervention to meliorate primary care direction of CKD and provide timely access to specialist advice.

The introduction of this unique virtual CKD clinic, based on sharing full access to the primary care tape, was followed past rapid take upward of the service by local GPs across all four participating CCGs. Improved access to specialist advice also included disadvantaged groups, such as care home residents, for whom traditional OPD attendance poses most difficulties. Clinic barriers to constructive assessment, such as lost notes, transport delays, language barriers and patient non-attendance simply disappeared. Time from GP referral to nephrology communication visible in the GP tape fell from 64 to 6 days. Surveys identified loftier rates of satisfaction from GPs with ease of clinic use, the value of timely specialist advice and increased conviction in managing CKD. Nephrologists valued seeing the entire patient record, particularly the eGFR graph, but were more affected past changes to traditional working practices and the loss of patient contact. Virtual assessment took somewhat less time than a traditional showtime outpatient appointment. Simply 12% of referrals required a subsequent face-to-face appointment, notwithstanding twoscore–50% of referrals had at to the lowest degree 1 virtual follow upwardly before discharge back to the GP. The service alter was highly successful in providing an expansion in the chapters to assess patients with kidney disease and provided rapid access to traditional outpatient services for the minor numbers who needed specialist investigation and follow upward.

Strengths and limitations

A force of this project is that all general practices beyond four contiguous CCGs took function. Hence this evaluation examines the application of a circuitous service modify to whole health economies, rather than just selected practices. The first year of the project involved three CCGs which already had a well-developed working relationship with the Clinical Effectiveness Group and the main care data management, exercise comparisons and facilitation services they offer [24]. Historically the clinicians and managers in these CCGs have been early adopters of clinical change of value to patients and the health economy. The project was slower to engage with the 4th CCG (Waltham Wood) where in that location was less experience of data sharing and system wide quality improvement work.

The programme evaluation was pragmatic, and allowed for some variation in the mode the intervention was implemented in each of the four CCGs. Identifying contextual differences betwixt CCGs in clinical leadership, and in their arroyo to incentivising change in their elective practices is important for the success of scaling up complex interventions such as this. Differences in context can bear upon the procedure of implementation and contribute to differences in speed of diffusion across differing geographical areas.

This evaluation is limited to the touch on on timely and inclusive access to kidney services. We practice not have information on the clinical outcomes for patients and recognise that a longer evaluation period is needed to fully empathize the impact of the change, over fourth dimension and confronting prior do.

Implications for practice and futurity research

Changes to the traditional patterns of delivering care volition involve a complex interaction between making the well-nigh constructive use of data inside the electronic health record (EHR) both in primary and secondary intendance, harnessing clinical leadership to develop novel care pathways, and utilising it to aggrandize patient engagement in their healthcare. The Wachter report [25] pointed out that digitisation is only one part of a whole system of change and that: "..implementing health IT is one of the most complex adaptive changes in the history of healthcare, and mayhap of any industry. Adaptive change involves substantial and long-lasting engagement between the leaders implementing the changes and the individuals on the forepart lines who are tasked with making them work."

Data collected for the project was used to better the system. Examples include the referral funnel plot which is used to place practise teams which might benefit from clinical visits, and the measurement of the 'hidden work' within virtual clinics which questioned the frequency of virtual follow up by clinicians. The learning health system we describe has implications for changes to clinical practice nationwide. Interventions such as this will all crave improvements to the interoperability of Information technology systems to deliver clinically useful real-time information for both GP practices and hospitals, and will benefit from regular facilitation to appoint clinical teams in the effective use of It for clinical quality improvement. They as well crave positive working relationships between managers and clinicians across primary and secondary care to enable the necessary date in data sharing for learning along the whole patient pathway.

Conclusions

The kidney service described here illustrates that it is feasible to develop 'virtual' specialist services past sharing access to the consummate primary care EHR. For such services to thrive they need support from community interventions which enlist primary care in a continuous process of service improvement, and hence can make best use of both specialist and generalist expertise. Replacing infirmary omnipresence for CKD with specialist review of the EHR appears adequate to patients. However, such 'virtual' services widen admission, increase referrals, and hence do not reduce the overall clinician fourth dimension needed for conclusion making. Further work is needed to ensure that the clinical outcomes for patients are at to the lowest degree commensurate with those in traditional out-patient settings. This community service has lessons for the efficient delivery of kidney services nationally. The full implications of such changes in the structure of care need further exploration before applying them to specialist clinics in other long term weather.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current report are available from the corresponding writer on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CCG:

-

Clinical commissioning group (https://world wide web.nhscc.org/ccgs/)

- CEG:

-

Clinical effectiveness group

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- CRS:

-

Intendance records system

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular affliction

- eGFR:

-

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- EHR:

-

Electronic health record

- EMIS:

-

Egton Medical Information Systems

- GP:

-

General practitioner

- IT:

-

Information technology

- NHS:

-

National wellness service

- OPD:

-

Out patient department

References

-

Nitsch D, Caplin B, Hull SA, Wheeler DC, Kim LG, Cleary F. National Chronic Kidney Disease Audit: National Report (part 1). 2017. http://world wide web.ckdaudit.org.great britain/files/4614/8429/6654/08532_CKD_Audit_Report_Jan_17_FINAL.pdf;

-

National Institute for Health and Intendance Excellence. Chronic Kidney Disease: Early Identification and Direction of Chronic Kidney Illness in Adults in Chief and Secondary Care. 182 ed. United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland 2014.

-

Lv J, Ehteshami P, Sarnak MJ, Tighiouart H, Jun M, Ninomiya T, et al. Effects of intensive claret pressure lowering on the progression of chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2013;185(11):949–57.

-

Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A, Anderson SG, Callender T, Emberson J, et al. Blood force per unit area lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-assay. Lancet. 2016;387(10022):957–67.

-

Baigent C, Landray MJ, Reith C, Emberson J, Wheeler DC, Tomson C, et al. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with simvastatin plus ezetimibe in patients with chronic kidney disease (written report of heart and renal protection): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9784):2181–92.

-

Department of Wellness. Longterm weather compendium of information. 3rd ed; 2012.

-

Department of Health. The NHS Long Term Plan. London; 2019. Available from: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.britain/

-

Harnett P, Jones One thousand, Almond Grand, Ballasubramaniam G, Kunnath V. A virtual clinic to improve long-term outcomes in chronic kidney disease. Clin Med (Lond). 2018;xviii(v):356–63.

-

Jones C, Roderick P, Harris Southward, Rogerson M. An evaluation of a shared main and secondary care nephrology service for managing patients with moderate to advanced CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;47(one):103–xiv.

-

Mark DA, Fitzmaurice GJ, Haughey KA, O'Donnell ME, Harty JC. Assessment of the quality of care and financial bear on of a virtual renal clinic compared with the traditional outpatient service model. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65(x):1100–7.

-

Gallagher H, Methven S, Casula A, Thomas N, Tomson CR, Caskey FJ, et al. A programme to spread eGFR graph surveillance for the early on identification, support and treatment of people with progressive chronic kidney disease (ASSIST-CKD): protocol for the stepped wedge implementation and evaluation of an intervention to reduce tardily presentation for renal replacement therapy. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(one):131.

-

Get Every bit, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of expiry, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. Northward Engl J Med. 2004;351(xiii):1296–305.

-

Friedman CP, Wong AK, Blumenthal D. Achieving a nationwide learning health system. Sci Transl Med. 2010;ii(57):57cm29.

-

Hole B, Gilg J, Casula A, Methven S, Castledine C. Chapter one United kingdom renal replacement therapy adult incidence in 2016: national and Centre-specific analyses. Nephron. 2018;139(Suppl 1):13–46.

-

Office for National Statistics. 2011 Census: KS201EW Ethnic group, local authorities in England and Wales. Available from: http://www.ons.gov.united kingdom/ons/publications/re-reference-tables.html?edition=tcm%3A77-286262.

-

Department for Communities and Local Regime. English indices of deprivation 2015 2015 Available from: https://www.gov.united kingdom of great britain and northern ireland/government/statistics/english-indices-of-deprivation-2015.

-

Kotter JP. Leading change: why transformation efforts fail. Harvard concern review; 1995(March–April). p. 59–67.

-

NHS England. GP contract data 2018/19 2018. Bachelor from: https://world wide web.england.nhs.uk/eu-leave/gp-contract/gp-contract-documentation-2018-19/.

-

Thomas N, Rajabzadeh V, Hull SA. Using chronic kidney disease trigger tools for safe and learning: a qualitative evaluation in E London primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69(687):e715–23.

-

Thomas N, Rainey H. Innovating and evaluating teaching for people with kidney disease. J Kidney Care. 2018;3(2):114–9.

-

Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron East, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the assay of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health enquiry. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:117.

-

Noble H, Smith J. Issues of validity and reliability in qualitative enquiry. Evid Based Nurs. 2015;xviii(2):34–v.

-

Hull SA, Rajabzadeh Five, Thomas Northward, Hoong S, Dreyer G, Rainey H, et al. Improving coding and primary care management for patients with chronic kidney disease: an observational controlled study in Due east London. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69(684):e454–e61.

-

Clinical Effectivness Group, Renal Health Service. Bachelor from: https://www.qmul.ac.britain/blizard/ceg/renal-wellness-service/.

-

Wachter RM. Making IT Piece of work: Harnessing the Power of Wellness Information Engineering to Improve Care in England. Study of the National Advisory Group on Health Information technology in England. National Advisory Group on Health Information technology in England; 2016.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the participating GPs for their cooperation, without which, such studies would be impossible.

The virtual service was piloted and developed past the nephrology team: Andrea Cove-Smith, Suzanne Forbes, Thomas Oates, Ulla Hemmila (Belfry Hamlets) Mark Blunden, Ravi Rajakariar, Sajeda Youssouf (Newham) Conor Byrne, Kieran McCafferty (City & Hackney) Gavin Dreyer, Hamish Dobbie, Raj Thuraisingham (Waltham Forest).

The authors are grateful for regular information extraction undertaken by Martin Sharp and Isabel Dostal at CEG, and for communication on data analysis from Rohini Mathur.

Funding

This study was supported by an Innovating for Improvement grant from the Health Foundation. The funders took no part in the analysis, estimation and writing of this report.

Author data

Affiliations

Contributions

The study was designed past SH, NA, SHo, Hr and NT. Data analysis was past VR. The report was drafted by SH. All authors, NA, SHo, GD, 60 minutes, VR and NT contributed to writing and review of the report. All authors accept read and approve the final version.

Corresponding writer

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Upstanding approving was non required for this service improvement evaluation. This is compliant with national guidance: http://www.hra-decisiontools.org.uk/ethics/resultN2.html. All patient-level data are anonymised, and only aggregated patient data are reported in this study. All GPs in the participating east London practices provide written consent to the use of their anonymised patient data for research and evolution for patient benefit.

Consent for publication

Not applicative.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Boosted data

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary data

Additional file 1: Table S1.

(a) Semistructured questionnaire for interview with GPs and nephrologists. Details of questions asked during i to one interviews with clinicians(b) General exercise survey questions. Details of 8 survey questions circulated to full general practices before long after the start of the service implementation. Figure S1. Kickoff appointments in general nephrology, numbers of virtual clinic and follow-upwards appointments for each of the iv CCGs participating in the community renal service: quarterly data 2014–eighteen. A graph showing the engagement data broken down for each of the four participating CCGs in the project.

Rights and permissions

Open up Admission This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Eatables Attribution four.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted employ, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided yous give appropriate credit to the original author(southward) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Eatables license, and indicate if changes were fabricated. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/one.0/) applies to the information made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Virtually this article

Cite this article

Hull, S.A., Rajabzadeh, V., Thomas, Northward. et al. Do virtual renal clinics improve access to kidney care? A preliminary impact evaluation of a virtual clinic in East London. BMC Nephrol 21, ten (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-020-1682-6

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-020-1682-6

Keywords

- CKD

- Principal care

- Virtual clinic

Source: https://bmcnephrol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12882-020-1682-6

0 Response to "Factors Affecting Resident Satisfaction in Continuity Clinicã¢â‚¬â€a Systematic Review"

ارسال یک نظر